This article describes the journey of School 360, a primary school which opened in Newham, London in September 2021. The school deliberately sought to do education differently, in terms of leadership, curriculum, pedagogy and assessment. They experimented with structures, practices and places to create an educational experience that would enable the children to develop better life skills, achieve higher well-being and be better learners, to provide a better community experience for parents, and enable a happier and more fulfilled staff.

This is the story of an unusual school, its special beginning and ongoing extraordinary journey towards a different kind of education for children in East London. In September 2021, School 360, an ordinary state-funded school within the Big Education Trust, opened in Stratford, London in an area of new development, with a remit from the developers to act as a community resource.

The first unusual thing about this school was that it had two Co-headteachers. Andi Silvain had previously worked in film and theatre, and then moved into teaching some 20 years ago. Born and bred in East London, her former role was as a Deputy Headteacher at School 21, just down the road. She had seen the challenges secondary schools face in supporting pupils who struggle to engage with even the most motivating and accommodating school experiences and wondered what it- might be like to start in Reception and support these pupils from the outset. Sarah Seleznyov had been teaching in various London boroughs for almost 30 years, in schools, as a local authority consultant, at UCL Institute for Education and the National Literacy Trust, and as Director of a Teaching School. A PhD student, she was interested in how schools can engage with research as a way to challenge the status quo of education policy. Both Headteachers applied as Co-Headship partnerships – but not with each other! They were split up from their partners at the interview and match made by the CEOs of the Trust.

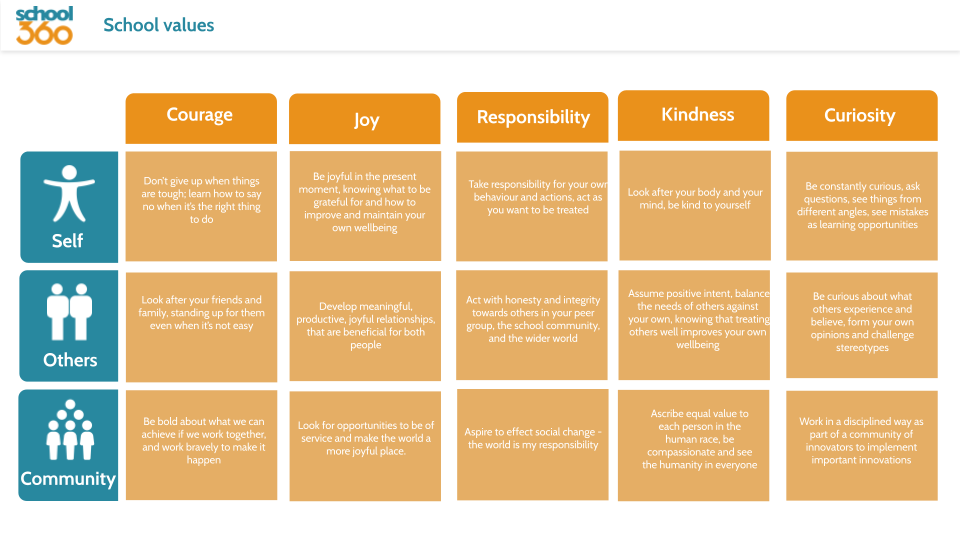

This could have been problematic: two people who have never met, working in a close partnership through an intensive design process for a brand-new school. And yet, they found that their values aligned perfectly and their skillsets were complimentary. The name School 360 was chosen by them to represent their joint commitment to educating the whole person: Head, Heart and Hand, and to be a school for and within the community. The first thing they committed to producing was a set of values which would underpin everything that happened in the school: leadership, behaviour, culture, curriculum and pedagogies (Hawkes, 2005). These values were described through three lenses: the self, the relationship with others, and with the community beyond the school:

The mission statement they created was rooted in these values: Learn together, think differently, change the world. Both Headteachers wanted to focus the educational mission for the school on social justice, developing pupil agency, so that pupils leaving the school had the confidence, skills and knowledge to fight for the things that mattered to them, to their families, to the community and to the world.

Beyond the focus on pupil agency, there were two distinct ways in which social justice would be enacted at the school. Firstly, a focus on recruiting a diverse staff

team, representative of the diverse community the school served. Applications for roles were blind scored, and consideration was given to the diversity of the team when selecting candidates. Opportunities were given to parents to develop their skills through volunteering at the school in various different roles. Work experience students from local schools and colleges would be welcomed and supported. There was a strong commitment to inclusion through the development of a values

curriculum (Hawkes, 2005), which would teach children about the protected characteristics from Reception up, through a weekly taught session for all classes.

This commitment to inclusion would also shape the broader curriculum, making it anti-racist, and anti-discriminatory in all ways. There would also be a different

type of governance. The Trustees for Big Education would do the heavy lifting in terms of statutory governance and legal responsibilities, leaving the school to focus on building a Community Panel. This panel of members of the school and local area would work with Citizens UK (Jameson and Chapleau, 2011) to identify and tackle issues that mattered to the local community, from street lighting to local parks, from recycling to food banks, from equity to enablement. Both the Panel and the Headteachers were committed to hearing all the voices of the diverse parent community. As a new school, no plans were set in stone, enabling the school to be responsive to parents’ views as it grew and evolved. It was often tricky to answer parents’ questions at open days:

‘How will reading be taught in Year 2?’

‘We don’t know yet – we have some ideas, but would want to hear what

parents think.’

Secondly, there was a commitment to tackling the climate crisis and supporting pupils and as part of this, supporting families to become more engaged with the natural world around them (Hand et al., 2019). The school grounds were developed as a natural playground for the many children who lived in flats, with no access to outside space. Thanks to a close partnership with an organisation called The Visionaries, a grand plan was put in place. An annual family camping trip was run, where parents camped with their children overnight. Funds were raised and a roof garden was developed and built by parent and corporate volunteers, and a family gardening club was run weekly. The school put chickens in the playground and drew together a group of committed eco-champions from across London to raise money to rewild the school grounds, to enable it to become a community resource on evenings and weekends, and to act as a model for sustainability for local schools. The rooftop garden planned to grow food for the kitchen which was run by Chefs in Schools, an organisation that seeks to improve school dinners by placing professional chefs into school kitchens to train catering staff to cook healthy delicious meals from fresh ingredients. We knew that many children living in urban environments would not understand where food came from and that for those living in deprived circumstances, fresh food wouldn’t always be available, so the food experience we would offer had to be high quality and delicious. Teachers and staff ate with mixed age cohorts at tables, avoiding the canteen-style experience of most schools, and teaching the children how to lay the table, serve each other, try new foods and clear away.

A curriculum was designed to enable the development of agency and to support this commitment to social justice.

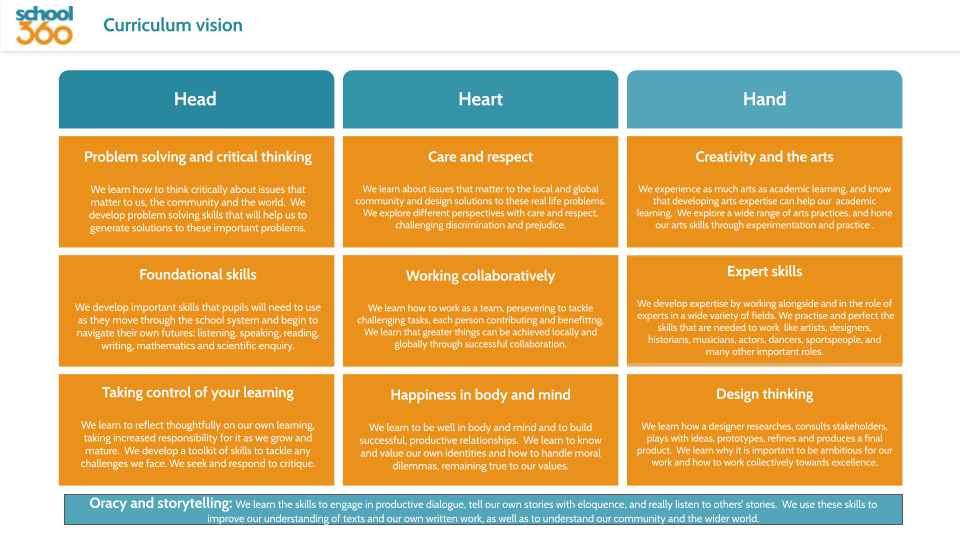

In line with the whole child 360 focus of the schools across the Big Education Trust, the curriculum considered Head, Heart and Hand in equal weighting. Wellbeing, relationships and health were as important as Reading and Writing, and of equal importance to the arts and creativity. Oracy and storytelling underpinned

the entire curriculum: pupils needed to learn to tell their own stories, to have their own voices and to listen to the stories and voices of others if they were to really understand and be inclusive in their approaches to the world (Golder at al, 2019). The curriculum intended to develop children as rounded human beings, not just high performing academically but also confident team players, who knew how to manage their own learning and to solve problems that matter.

How was the Heart curriculum enacted? Daily check-ins using the Zones of Regulation (Kuypers, 2011) enabled pupils to understand and articulate their emotions, supporting better behaviour and relationships. Twice daily mindfulness practice (Kuyken et al., 2013) supported pupils to remain calm, to more confidently face whatever challenges life threw at them, and to appreciate small pleasures. There were no stickers or charts to identify good and bad behaviours since both headteachers agreed that extrinsic motivation (Deci, 1972) did not work. When a child did behave in a negative way, the Zones of Regulation were used to identify the underpinning reason for the negative behaviour, mindfulness techniques were used to calm the perpetrator and the victim, and a restorative conversation (McCluskey et al., 2008) took place.

The Hand curriculum relied heavily on the project-based learning approach (Berger, 2003) and its associated pedagogies:

Instead of teaching in subject silos and working systematically through National Curriculum subject content, learning was shaped by projects about problems that were important to the children, their communities and the world around them. They explored these problems with the support of outside experts from diverse disciplines, so they could end up getting advice and feedback from ballerinas, archaeologists, divers, chefs, accountants or any number of experts. They would work towards the production of a final product of which they could be proud: a dance, a presentation, an object, a piece of writing, a podcast. They would achieve this through engaging in feedback loops, practising skills over time, revising and improving their final drafts with the help of experts, peers and teachers. In the first term, the first Reception class worked on multiple iterations of a self-portrait, giving each other feedback: ‘Your skin is the right colour but maybe next time remember eyebrows?’ They presented all the iterations of their portraits at an exhibition for their families, where the parents could also give feedback on the final portrait. In the second term, they designed buildings for the development being built around the school. They had a workshop with real builders who helped them do carpentry, tiling, plumbing and bricklaying. They presented their building designs to the architects of the development, and received feedback from them on the suitability of these ideas, which included a zoo, a library and many more innovative ideas. The school uniform was developed by a team of graduates from the London College of Fashion who carried out interactive consultative workshops with children and parents to hear what they wanted, considered sustainability, cost and choice and designed a brilliant uniform for the school.

Across the curriculum, play played a vital role. The headteachers were committed to play as a crucial way to support learning across the curriculum and

for all ages (Parker and Thomsen, 2019). They also felt that England formalised learning much too quickly and that a play-based continuous provision curriculum was a much better way to enable learning for all young children, not just for those in Reception classes, as long as adults were carefully supported to engage with all children in an effective way (Poweret al., 2019). In order to enable this, the school adopted a very simple but very powerful approach to professional development. All staff explored research and readings about effective adult interactions in a play-based learning environment, largely drawing on the TRAIL (Teaching Professionals Reflecting on Agency in Learning, Baker et al., 2021). All staff, from leaders, to teachers, to teaching assistants, responded to the research input by videoing themselves interacting with children. These videos were then shared in weekly professional development sessions, where all staff reflected on the videos, related this to the research material and set collective and personal goals for improving their interactions with children. This created a flat hierarchy: teaching assistants critically analysed headteachers’ practice and made suggestions to them on improving their practice.

Just as all staff were included in the same learning experience, so were all children. Based on research into the potentially negative impact of splitting children

by achievement level (Marks, 2016), the headteachers set an expectation that all lessons would be low threshold and high ceiling (Boaler et al., 2021). Low-achieving children would never be taken out of whole class teaching experiences to experience a different curriculum offer, as this would just mean them taking a different and less challenging trajectory, from which they would never return. If they needed extra help, they would receive it in the form of increased and carefully planned adult interactions in the play environment. This put school policy at odds with the expectations for example of synthetic phonic programme providers – and yet, the

children’s progress showed that this was working. Less children fell behind, and both progress and attainment were strong across the board. High-achieving

children were also challenged through the feedback loops the teacher created. Using the Seesaw app, a small number of ‘must do’ tasks were set each week online. Children would undertake these tasks on a day and at a time of their own choosing, upload their tasks using video, audio or photographs and submit them to the teacher, the concept of choice being one of the key features of playful learning (Zosh et al., 2019). The teacher would then provide personalised feedback to which children would respond, editing and improving their work.

The Seesaw tool also enabled us to work in partnership with parents. Parents could see all the work that children completed at school on their phones, using the

app. Children could upload homework or home learning evidence to the app using their parents’ phones. In this way, learning was shared across home and school, creating a powerful partnership (Van Poortlviet et al., 2018). The school also wanted to rethink other sorts of communication with parents with the aim of increasing pupil agency and improving parental relations (BESA, 2016). They set a goal that by the end of Year 6, children would be confidently writing their own reports and began by setting up each child with their own website and asking them to discuss with their teacher what they would like to add to this site and why. As the children were so young, the teacher scribed their thoughts and evidenced it using the work they had already posted on Seesaw. Instead of the usual long and jargon-filled document that most parents receive at the end of the school year, each family were able to view their own child’s website, seeing the next steps the child and the teacher had set together, and sharing in their child’s pride at their own achievements. It also saved teachers four days of workload each year, workload that usually eats into their own free time.

With a similar aim in mind, parents’ evenings were cancelled. A ten-minute meeting twice a year which involved very tired teachers staying on at school until 8 pm did not seem to provide the optimal way to maintain communication and partnerships with parents. Instead, a system of weekly focus meetings was set up. At the beginning of the week, the teacher would identify three focus children and call their parents to let them know and find out if there was anything going on at

home that should be taken into account. All adults in the setting would then focus on observing those children during that week. The teacher would share this evidence with the parent in a short face-to-face meeting at the end of the week. This meant children about whose progress the team were concerned could be focused on at the start of term, and there was more regular communication with parents across the year, without the need for exhausting late nights for teachers.

How has doing things differently been, for parents, for children and for staff?

Our children are still too young to be surveyed, but what we do know is that they present as happy and that their attainment and progress is strong. One in three of our pupils are eligible for free school meals, significantly above the national average, reflecting some of the social and economic challenges in the community and yet, in our first year, 73% of our Reception children achieved a Good Level of Development – on entry, only 35% of children were on track. Our first parent survey highlighted that 85.7% of parents feel very supported or supported by the school. It’s HARD to do things differently, and the expectations of staff are high. They have been tired at times but always felt fulfilled and excited about the journey, as well as happy that consideration has been taken for their workload. School 360 will always be a work in progress, but we think it’s worth it, as it really has helped the pupils’ learning and well-being, and we wouldn’t have it any other way..

Sarah Seleznyov and Andi Silvain are Co-headteachers at School 360. Andi was formerly Deputy Head of the Middle School at School 21, London. Andi is an advocate of the arts and prior to teaching, she worked in television and theatre. Sarah formerly led the London South Teaching School Hub, based in Southwark. She has also worked in school improvement, for the National Literacy Trust and at UCL Institute of Education. She is studying for a PhD at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.

REFERENCES

Baker, S.T., Le Courtois, S. & Eberhart, J. (2021) ‘Making Space for Children’s

Agency with Playful Learning’, International Journal of Early Years Education,

pp. 1–13.

Berger, R. (2003) An Ethic of Excellence: Building a Culture of Craftsmanship

with Students. NH: Heinemann.

BESA. (2016) Parents Call for Teachers to Rethink the Traditional Primary School

Report. Available at: https://www.besa.org.uk/news/parents-call-teachersrethink-traditional-primary-school-report/ [Accessed on: 27 November 2011].

Boaler, J., Dieckmann, J.A., LaMar, T., Leshin, M., Selbach-Allen, M. & PérezNúñez, G. (2021) The Transformative Impact of a Mathematical Mindset

Experience Taught at Scale. In Frontiers in Education (p. 512). Frontiers.

Deci, E.L. (1972) ‘Intrinsic Motivation, Extrinsic Reinforcement, and Inequity’,

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 22(1), p. 113.

Golder, G., Briggs, D. & Child, S. (2019) ‘The Plymouth Oracy Project: Its Impact

on Non-academic Measures of Pupil Success’, Profession, 18, p. 19.

Hand, K., Freeman, C., Seddon, P., Recio, M., Stein, A. & Van Heezik Y. (2019)

‘Are City Kids Missing Out on Nature?’, Frontiers for Young Minds, 7, p. 71.

DOI: 10.3389/frym.2019.00071

Hawkes, N. (2005) Does Teaching Values Improve the Quality of Education in

Primary Schools? (Doctoral Dissertation, University of Oxford).

Jameson, N. & Chapleau, S. (2011). Engaging Citizens to Ensure our Democracy:

The Role and Potential of Education Institutions. Citizens UK: London

Kuyken, W., Weare, K., Ukoumunne, O.C., Vicary, R., Motton, N., Burnett, R.,

Cullen, C., Hennelly, S. and Huppert, F. (2013) ‘Effectiveness of the Mindfulness

in Schools Programme: non-randomised controlled feasibility study’, The

British Journal of Psychiatry, 203(2): pp. 126–131.

Kuypers, L. (2011) The Zones of Regulation. San Jose: Think Social Publishing.

Marks, R. (2016) Ability-Grouping in Primary Schools: Case Studies and Critical

Debates. Critical Publishing.

McCluskey, G., Lloyd, G., Kane, J., Riddell, S., Stead, J. & Weedon, E. (2008)

‘Can Restorative Practices in Schools Make a Difference?’ Educational Review,

60(4): pp. 405–417.

Parker, R. & Thomsen, B.S. (2019) ‘Learning through Play at School: A Study of

Playful Integrated Pedagogies That Foster Children’s Holistic Skills

Development in the Primary School Classroom.

Power, S., Rhys, M., Taylor, C. & Waldron, S. (2019) ‘How Child-Centred

Education Favours Some Learners More Than Others’. Review of Education,

7(3): pp. 570–592.

Van Poortlviet, M., Axford, N. & Lloyd, J. (2018) ‘Working with Parents to Support

Children’s Learning: Guidance Report.

Zosh, J.N., Hopkins, E.J., Jensen, H., Liu, C., Neale, D., Hirsh-Pasek, K., Solis,

S.L. & Whitebread, D. (2017) Learning through Play: A Review of the Evidence.

Billund, Denmark: LEGO Fonden.

Big Education Trust is a company limited by guarantee registered in England and Wales.

Company registration number: 07648389.

VAT number: GB142676505

Registered Office: c/o School 21, Pitchford Street, London E15 4RZ

Privacy Policy | Terms & Conditions

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |